|

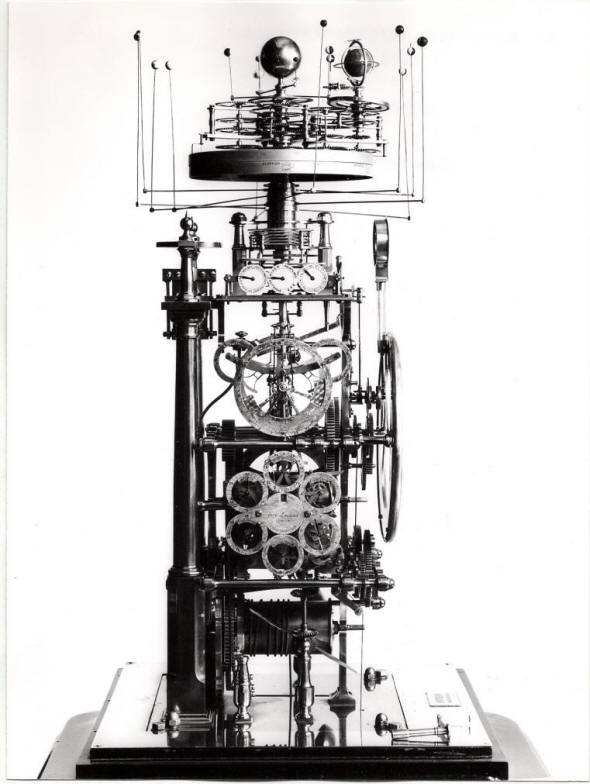

POUVILLON RESTORATION PROJECT - August 2011 A discussion about the origin of the tellurion assembly Below is shown the tellurion and orrery subassemblies. The tellurion is the upper section above and including the porcelain dial and and metal rings. This depicts the Sun-Earth-Moon system as well as the two inner planets of Mercury and Venus. The orrery is below the rings and are comprised of the multiple planetary attachment collets as well as the orrery wheel pack below. This depicts the rest of the outer planets, Mars, Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus, Pluto. (This was created before the controversy of demoting Pluto from a planetary status). I am using the term for the upper section as the tellurion liberally, as in the strict sense a tellurion would only encompass the Sun-Earth-Moon system and not the inner two planets of Mercury and Venus. I'm not sure if there is a specialized term for this type of model.

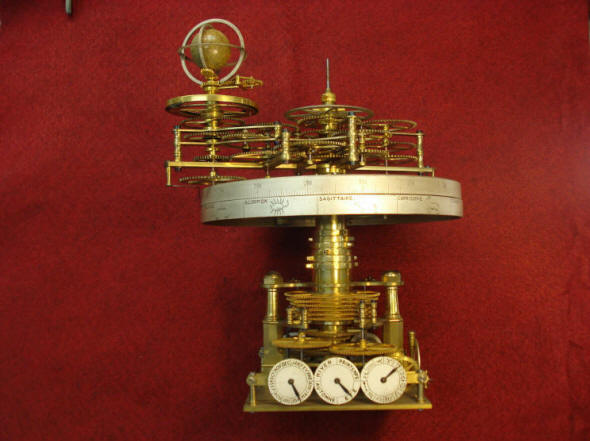

Shown here is the tellurion/ orrery unit dismounted from the rest of the clock. The first photo is the front, along with the leap year indicator. the second the rear.

First photo is the right side with the unequal hours dial, day of week and the days zodiacal sign. The unequal hours dial represents the state of the strike train. In fact if one were to look at the strike count wheel mounted to the strike train's main wheel, it would match exactly to this dial. We think that this dial was used to correlate and make corrections to readings on the other complications that are driven off of the strike train. Next photo the left side with the month, seasons and month's zodiacal sign.

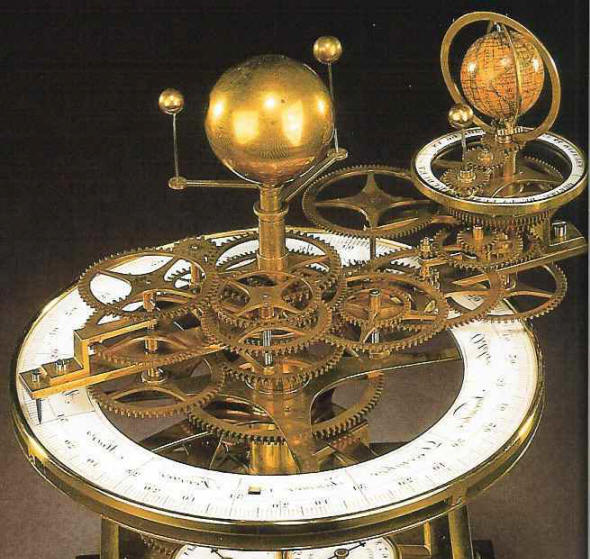

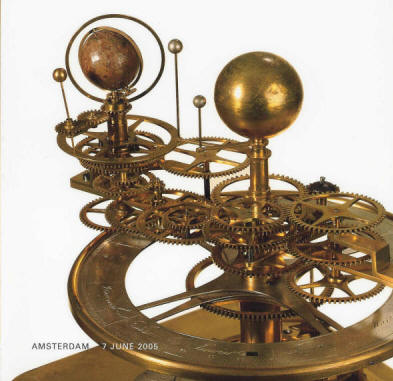

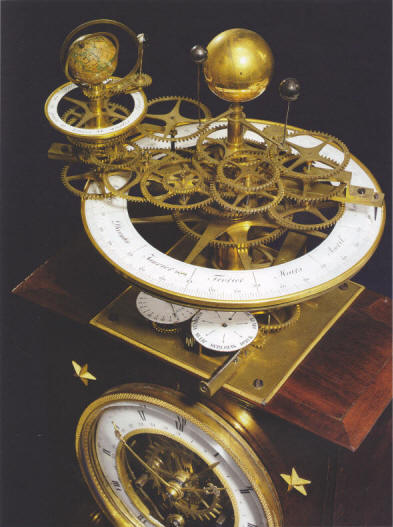

We now get to the reason for this page. It comes to no one's surprise that doubt was cast immediately about this component being made by Pouvillon. Enamel dials do not appear anywhere else on the clock. A quick search of my horological records found four virtually identical examples. The first photo is an overview of the Pouvillon tellurion. The second photo is a tellurion that is part of a mechanism signed by by Antide Janvier, c. 1790 as pictured in Christie's catalog in June of 1996. Notice the many similarities, especially in the enamel dials as well as the dial support cross. They are, in fact, identical. The wheel construction is also identical and these wheels differ from the other spoke designs in Pouvillon's clock. The paper-covered Earth as well as the Sun (not shown) are identical. There are some differences in the construction of the wheel frames and frame pillars, with Pouvillon's a bit more refined. The fourth photo shows another nearly identical orrery on top of a clock signed by Ferdinand Berthoud as pictured in Sotheby's catalog in June 2005 and dated circa 1835. The only difference is the latter uses an engraved brass dial verses the enamel dial; everything else is identical. Fifth photo shows an example attached to a clock signed by Baltazar Pere c. 1810, and in the sixth photo one by Giteau, c. 1825 So clearly these four examples as well as the one used by Pouvillon were made by the same hand. The Janvier example predates the Berthoud example by over 40 years - a long period of time for one maker to have been producing these. Perhaps the Berthoud firm (Berthoud had been deceased since 1807) did something similar to Pouvillon and reused the tellurion to top off that clock in the same manner. So who made the tellurion? It could have been Janvier, Pere, or Giteau but it is likely a third party was the supplier to these these makers. Note the single, lower plate with the four corner screws in the last two examples cited above. All of the tellurians have these same corner fastening holes. In 2024 I was sent photos of a tellurion that met all the criterion of those that were made for the various makers. it looks to have been made as a model by what may be the original supplier for these tellurions.

As one can see this example has all of the characteristics of the various tellurions depicted by many clock makers, right down to the shape of the cocks, diameter of dial work. It is obvious that the demonstration knob is a 20th century replacement. The fact that this was mounted to a purpose-built stand seems to indicate that this was meant as a demonstration model. The name on the base is "DUCRETET A PARIS". A look up in the reference book Watchmakers and Clockmakers of the World, Brian Loomes, shows no entry for this name. The closest is Ducret, simply showing Paris 1812 as well as a reference to a maker in Switzerland of wooden clocks c. 1700. A search through ChatGPT also revealed nothing. It is a thin reed to hang an assumption on simply because a tellurion fitting all of the criterion is mounted to what looks to be a demonstration base of concurrent age, that is about 1800. Witness marks appear to conform that this was an original mounting, not something that was substituted for another item displayed before.

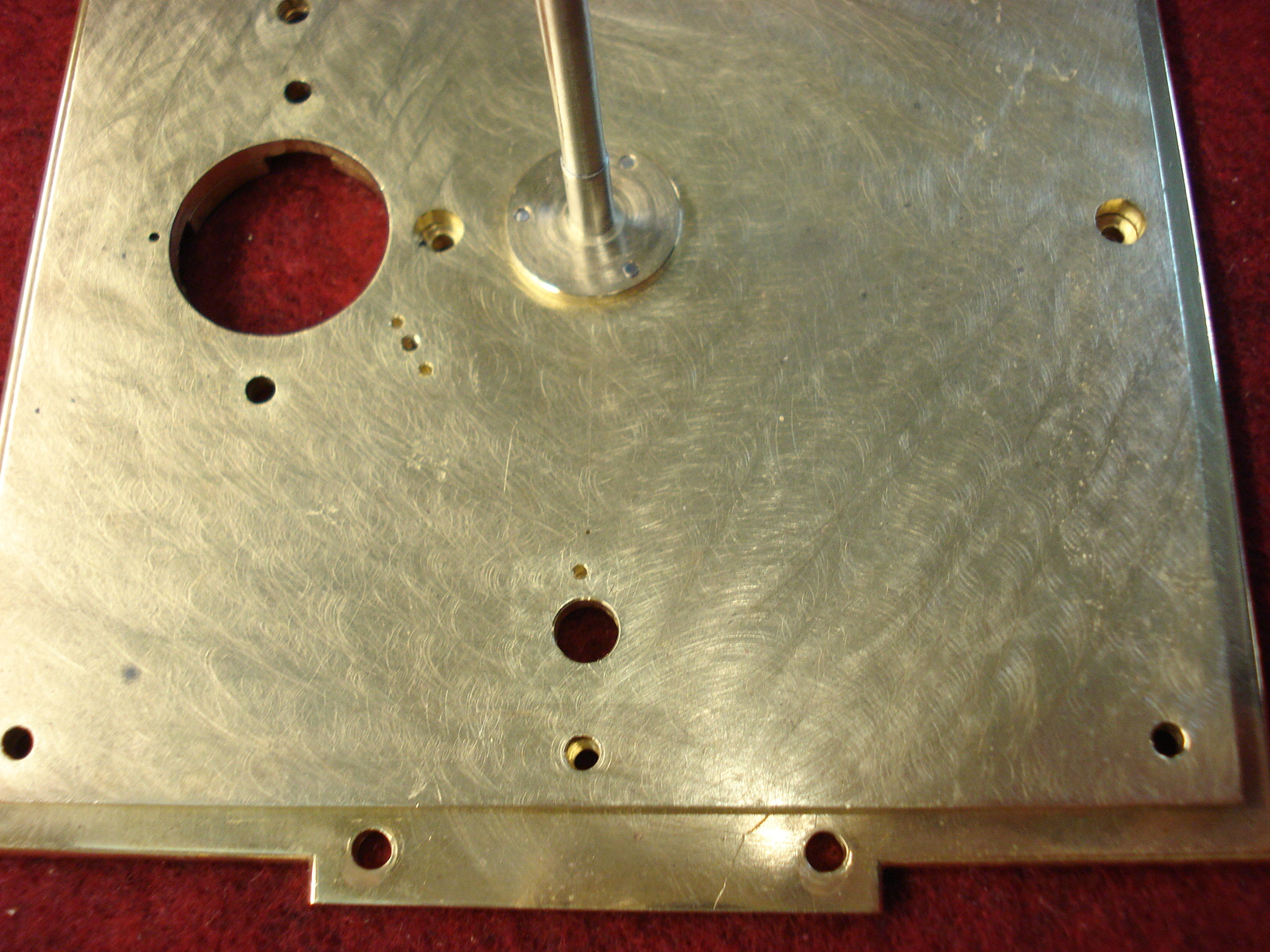

These three photos show the same area in the Pouvillon clock. The first photo shows the sandwiched double plates. Note the corner holes in the upper plate in the same positions as the examples cited in the preceding paragraph. The upper plate is the original that came with the tellurion which Pouvillon had added to his clock. The lower plate shows the extension necessary to attach the assembly to the rear of the clock frame. The next photo shows the upper plate removed and reveals the lower plate Pouvillon had made. He did this in order to be able to extend the area forward and rearward needed to meet the clock frame as represented by the circular steel area that join to the two extended forward corner sections as well as the rear support frame. The third photo shows the two plates joined with a close up of the extended corner section of the lower plate Pouvillon created to secure the tellurion assembly to the front clock frame. But what about the the now four empty, original corner holes? These must have bothered Pouvillon for a long time, since we know that in between 1948 and 1953, the period which we call the Phase Four of his construction of this clock he added two banks of dials which were each neatly mounted within these holes. In fact, throughout our forensic investigation of the clock we find only one instance of Pouvillon filling a misplaced hole. Apparently he felt that if he did not make the mistake, he must use the extant hole in some way. Assuming the tellurion was attached to the clock sometime before 1930 as described in Phase Two of the construction, he waited at least nineteen years to finally figure out how to use these holes for attachment points. As for further speculation, I wondered why Pouvillon had left this plate assembly in such a rather solid configuration, considering he went though so much trouble to skeletonize as much as possible the remaining areas of his clock. Perhaps since this was early on in his project and he felt unsure as to how to proceed, or perhaps a double, sandwiched plate may have not looked aesthetically correct. Clearly in hindsight he could have disposed of the original upper plate and mounted the components to his remade lower plate, and then skeletonized the whole. The second photo above shows a vast area that could have been eliminated. It is also clear Pouvillon has added the star shaped lower base which supports the dial This was probably done to introduce an area where the thirteen blued steel pointers are mounted; these pointers could well have been watch hands, see first photo below. They deal with the ecclesiastical calendar dates in connection with the stages leading to and after Easter, the moveable feasts and fasts. Each pointer has an abbreviation as to it's indication as follows:

The moveable feasts outlined above cover a two month period prior to and after Easter, for a total of about 120 days, covering one-third of the 12 month enamel dial. A small pinion provided with a winding square is located behind this bank of pointers and allows one to adjust the pointers back and forth to correspond with the dates as they changes from year to year on the calendar dial, hence the term moveable feasts and fasts. The pointer hand attached to Paques is different from the rest. Until we deciphered the remaining pointers we had thought this was a later replacement. However as this pointer is attached to the most important feast day of the ecclesiastical calendar, it is probable Pouvillon did this purposely. In the photo the pinion is cranked fully in the direction of sending the pointer array to the earliest dates. A check on the possible dates of the moveable feasts, indeed shows the earliest date that Septuagesima Sunday can fall is January 18th and the latest February 21st. He also made the seven pointed star ring which resides just below the two inner planets of Mercury and Venus. It is engraved 0 to 360. The purpose of this ring is currently unknown. Also the planet attachments are clearly by Pouvillon and differ in design as well as the color of material from the rest of the tellurion as well as Janvier's example. More on these curious attachments below. Note the filled in square area just to the left of the number 31 and to the right of the 1 both located in the month of January. It is identical to the open square aperture in the photo of Janvier's device from the Christie's catalog. In Janvier's dial that square is slightly smaller and there is in addition to the number 1 on that dial, also the number 8 just after it. According to the auction catalog the number 1 through 100 are engraved on a ring that rotates below this aperture. I believe the catalog meant to say 00 through 99. In this way one has the year indication from 1800 through 1899. Since Janvier made his tellurian c. 1790 he would have had a full one hundred years before that complication became obsolete. He may have even had a removable number 7 painted over the 8 for the first 10 years after construction The filled in section in Pouvillon's dial is slightly larger and obscuring what would have been the 8 numeral and leaving only the 1. Pouvillon began the majority of the work on this clock in 1930, however, it is likely that the main clock was made several years earlier. There will be a further discussion about the time line of construction in a later installment. We believe that Pouvillon wanted to preserve this complication, but make it relevant to the 1900's. This could be done by obscuring the numeral 8 and replacing the original date ring with 9 through whatever numbers could be fit into the balance of the space on the ring. Pouvillon was keen to cram as many complications as he could into his clock and this function was not duplicated elsewhere within the clock. We believe that Pouvillon would not have so crudely covered up the aperture and certainly had no reason the enlarge it before doing so. Even if one assumes that the tellurion was missing the date ring or the components to drive it when it came into Pouvillon's hands, we know that he had the skills to reproduce these components and given the enlargement of the aperture we believe that the clock had this modified complication. We know the clock fell into disrepair and was in pieces in a charity shop for some period of time. We also so know that one other major component was lost sometime between the death of Pouvillon in 1969 and its first appearance in Jean-Pierre Rochefort's clock shop in 1983. Therefore we think that a later 'repairer' not having the ability to either repair or make the missing components decided to simply cover up the aperture. This project is focused in restoration, however, where we know components to be missing or strongly suspect so, we will make those components in a manner as most sympathetic to what we can infer as Pouvillon's original intent. It certainly is not difficult to take the annual rotational feed from the tellurion boom to move the date ring one notch per year. The next curiosity is the strange double-armed collets used to connect the planets on both the tellurian and the orrery. These were part of Pouvillon's original intent as we have a photograph taken from a newspaper clipping in 1953 of Pouvillon when he would have been 75 years old with his clock. One can clearly see the collets, although only one of each pair of arms are used to hold a planet, the other is empty. Also missing in this photo are the set of three small dials showing the state of the strike, the day and its zodiacal sign. Perhaps the clock was in partial disassembly during this time. When the clock appears in Jean-Pierre Rochefort's shop in 1983 these empty collets were filled with an identical planet. for a total of 17 planets rather than the correct number of 9. The Earth is unaffected by this. Without further historical evidence it is difficult to fathom the purpose of these empty holders. One obvious solution would be for counter weights. This is possible but as one can see the planets are small with fine wire used for attachments so they do not weigh much. There would be no need whatsoever for these on the two very short arms connected to the inner planets of Mercury and Venus. Another idea is that these empty holders were meant to hold a pointer that would be read off the tellurion ring bands to show where the planets are in the zodiac. This could also give purpose to the upper, smaller graduated ring of 3600 located below the two inner planets. The tellurion ring also is graduated with markings to 3600 . One could read the opposite end pointer of each of the two inner planets off the small ring, say Mercury's pointer was at 2700 and go directly to that same number on the larger, upper tellurion ring and then read off the lower ring the zodiacal house. We have no other ideas at this point and we believe that even if Pouvillon had originally had a purpose for these extra holders and then later abandoned the idea, he would have shaved off the extra arms. It would have been easy to do and would eliminate what otherwise is a rather awkward looking situation if left empty. On the other hand, he did not shave off the redundant count wheel pins on the strike train main wheel when they were replaced by the later-added slotted count wheel ring. Until further evidence is uncovered we have no other comment. |